- Remdesivir went from potential Ebola treatment to offering modest benefits for people with COVID-19.

- Drugmaker Gilead Sciences Inc. began research on remdesivir in 2009.

- Later testing showed that the drug had broad-spectrum antiviral activity.

All data and statistics are based on publicly available data at the time of publication. Some information may be out of date.

Remdesivir, a drug that once offered hope against Ebola, is now in the spotlight as the only current effective medication for COVID-19. But experts caution that it’s no “silver bullet” against the disease caused by the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2.

The drug’s history, though, shows the long and arduous path that compounds take from initial development to reaching the marketplace — a journey that many of these potential drugs never finish.

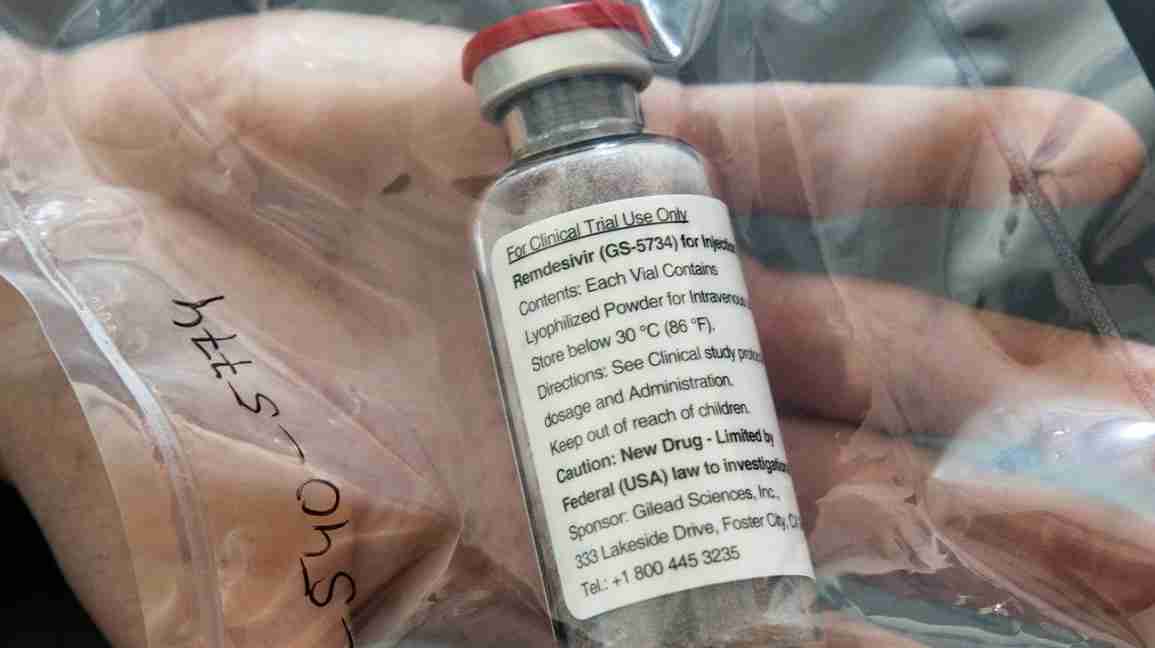

Drugmaker Gilead Sciences Inc. began research on remdesivir in 2009, as part of research programs for hepatitis C and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Later testing showed that the drug had broad-spectrum antiviral activity.

This led to initial animal studies against the Ebola virus. The drug, though, failed to live up to expectations, coming up short against two other drugs in a landmark clinical trial published last year.

Even before COVID-19, Gilead had tested remdesivir against other coronaviruses — including those that cause SARS and MERS — in laboratory and animal studies. However, no clinical trials were done because there were too few MERS cases and no SARS cases at the time.

At the beginning of this year, when scientists determined that the new pneumonia-like illness in China was caused by a coronavirus, Gilead provided remdesivir to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention to test the drug against the virus.

Remdesivir is thought to interfere with the mechanism that certain viruses, including the new coronavirus, use to make copies of themselves. Scientists are still working out exactly how that occurs.

Since January, additional laboratory studies and multiple clinical trials with remdesivir have been started. The results of some of these trials have been published, with some promising signs.

In late June, Gilead officials announced the company will charge $2,340 for a typical treatment course for people covered by government health programs. The charge will be $3,120 for people with private insurance plans. The amount people would pay out of pocket would depend on their insurance coverage, their income, and other factors.

Two studies on remdesivir were released last month. A Chinese study published in

But a preliminary report published in The New England Journal of Medicine showed that remdesivir shortened recovery time for people with COVID-19 from an average of 15 days to about 11 days.

Half of the patients in the study received remdesivir, the other half received an inactive placebo.

Study sub-investigator Dr. Robert M. Grossberg, an associate professor of medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and an infectious disease specialist at Montefiore Health System, said the results of this trial are “preliminary, but very promising.”

“This was a well-designed study that proved that an antiviral drug could improve outcomes in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19,” he said.

As for whether it keeps people from dying, he said the study “suggested that there might be a mortality benefit, but that wasn’t quite proven yet.”

In early June, Gilead announced that other data showed that people with moderate COVID-19 recovered more quickly when given the drug for 5 days, although the benefit was “modest.”

A 10-day course of the drug also improved patient outcomes, but the change wasn’t statistically significant. Patients in this study were hospitalized but didn’t need mechanical ventilation.

The data from this study hasn’t been published in a peer-reviewed journal, so it should be viewed with some caution.

Questions still remain about remdesivir, such as which patients might benefit most from the drug.

Grossberg said preliminary results from the NEJM study suggest that patients receiving supplemental oxygen, but not yet intubated or in critical condition, responded better while on the drug.

Dr. Marc Siegel, an associate professor of medicine at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, said based on what he’s seen with his patients, he already had a sense that remdesivir would work better when given earlier.

“By the time people come into the ICU, the virus has often already come and gone,” said Siegel, “and it’s more the body’s immune response to the virus that’s doing the damage.”

Ideally, he said, people would take the drug before they show up in the hospital — which is often 2 weeks into their illness. But currently, remdesivir is only available as an IV drug, not an oral medication.

Most COVID-19 studies have looked at treating people who have already been hospitalized. This misses many of the

“Identifying which patients would benefit from early treatment, and having safe and easy-to-use drugs to treat outpatients before they are hospitalized, would go a long way in making this infection less frightening and more manageable,” said Grossberg.

Another question about remdesivir is whether people will be able to afford it, especially the millions of Americans who are underinsured or uninsured.

There’s no price set for the drug yet. But the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), a private, nonprofit organization, recommended that a 10-day course of the drug be priced anywhere from $10 to $4,500.

Additional clinical studies are focused on the damage done by the immune system that Siegel mentioned, what’s known as a “cytokine storm.”

One study is combining remdesivir with baricitinib, an anti-inflammatory drug that’s approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis. Montefiore and Albert Einstein are taking part in that study.

Remdesivir would target the replication of the virus. Baricitinib would try to quell the body’s immune response, which is thought to be responsible for some of the damage to the organs that occurs with COVID-19.

“Combination therapy may prove to be an important strategy in the treatment of COVID-19,” said Grossberg. “Especially in severe disease where there may be need for the antiviral and immunomodulatory approach.”

Siegel doubts there will ever be a single “silver bullet” against COVID-19. So until we get a vaccine, he said combination therapy will offer the most benefits.

Still, he doesn’t expect the benefits of combination therapy to be that large — maybe a 10 to 15 percent improvement.

“In the end,” he said, “what it really comes down to is your comorbidities and your age, and how much support we can give you from a respiratory standpoint.”