How we see the world shapes who we choose to be — and sharing compelling experiences can frame the way we treat each other, for the better. This is a powerful perspective.

When Sydney City Council Inclusion Advisory Panel expert Mark Tonga said, “Perhaps sooner than you think, the ‘d’ word will be as offensive as the ‘n’ word is now,” Black disabled people across the English-speaking world rolled their eyes in sync.

Ableism is not the same as racism.

What actually exists in this semantic gymnastics of comparing disabled or any “bad” word with the n-word, is another level to racism — one that only exists within the disabled community.

We are used to the erasure of the black community in disabled spaces, and while we shouldn’t be accustomed to the blatant racism that often colors disability activism — here we are.

The comparison of disabled and the n-word is a shockingly bad attempt to co-opt the black experience.

“Disabled is like the n-word” conflates the two oppressions, in the way #AllLivesMatter blankets marginalization. To paint all oppressions as the same ignores the intersections disabled black people face.

As Rewire News noted, the medical industry provides treatment for black people based on erroneous beliefs like “Black people feel less pain.”

It’s important to note that while not all blackness is alike, the way racism, ethnocentrism, and xenophobia affect how people of color with dark skin live and survive, is a depressing constant worldwide.

There are many Australians of African descent in the country, but indigenous people in Australia have been called “black” by white people since colonization.

Moore’s understanding of the “n-word” and how the gravity of it is offensive may be somewhat removed from the ingrained relationship it holds in the United States. But the internet and Google still exist.

American pop culture reigns dominant and any cursory search of the term as it relates to disability, or racism as it informs ableism, could have offered some clue as to how wrong this trajectory is.

The “n-word” is steeped in oppression and conjures generational memories and trauma among African Americans. If we mix that in a cocktail of ableism and let people believe they’re interchangeable, we will remove black disabled people and their needs from the disability conversation even more.

It’s not enough to just have black or disabled representation — we need both

In the fight for representation, white disabled people often react with glee as white disabled people grace their screens. (It’s difficult enough for disabled white talent to be on screen, and black entertainers and filmmakers are even less likely to include black disabled people.)

But when black disabled people and people of color question where their representation is, we’re either told that yet another white guy should be representation enough or to wait our turn.

And, when a black celebrity or high profile person is caught being a perpetrator of ableism, like Lupita Nyong’o was, white disabled people quickly tone policed her portrayal of Red in “Us.”

This was a unique moment for the media to listen to disabled black voices, but instead, it became an either/or situation, where disabled black people were seen as defending ableist actions of black people.

But still, my experience is a markedly American take, so allow me to bring it home for the Sydney City Council

Racism and ableism are still rampant in Australia and indigenous people face institutionalized and medicalized racism that informs their ability to receive care.

Over the past few years, Australia has been lambasted in the media for its rising tide of white nationalism, Islamophobia, and racism — and to think that those bigotries don’t inform how service providers and doctors administer care would be dangerously wrong.

The average indigenous person in Australia dies 10 to 17 years earlier than a nonindigenous person and has higher rates of preventable illness, disability, and disease.

And, if we’re honest with ourselves, this is a global constant: the darker you are, the more likely you are to become disabled. Indigenous people also face doctors that don’t believe them and often brush aside patient concerns until they’re dire diagnoses.

A study of the

There are more pressing issues to address about race and ableism than confusing a slur with an identity

There are many disability advocates in the English-speaking world, both in Australia and beyond, that are revolutionizing how we see disability and are proud to call themselves disabled.

Trying to remove the word from our vocabulary and calling it advocacy is like painting one wall in one room of a house and calling it a total home makeover. If Lord Mayor Clover Moore is seriously considering the word ‘disabled’ to be thrown out in favor of ‘Access Inclusion Seekers’ (which is also problematic as “seekers” is a slur against people with addictions), then the council should also diversify the voices they’re listening to.

More importantly, they should let disabled people — specifically those of color — speak for themselves.

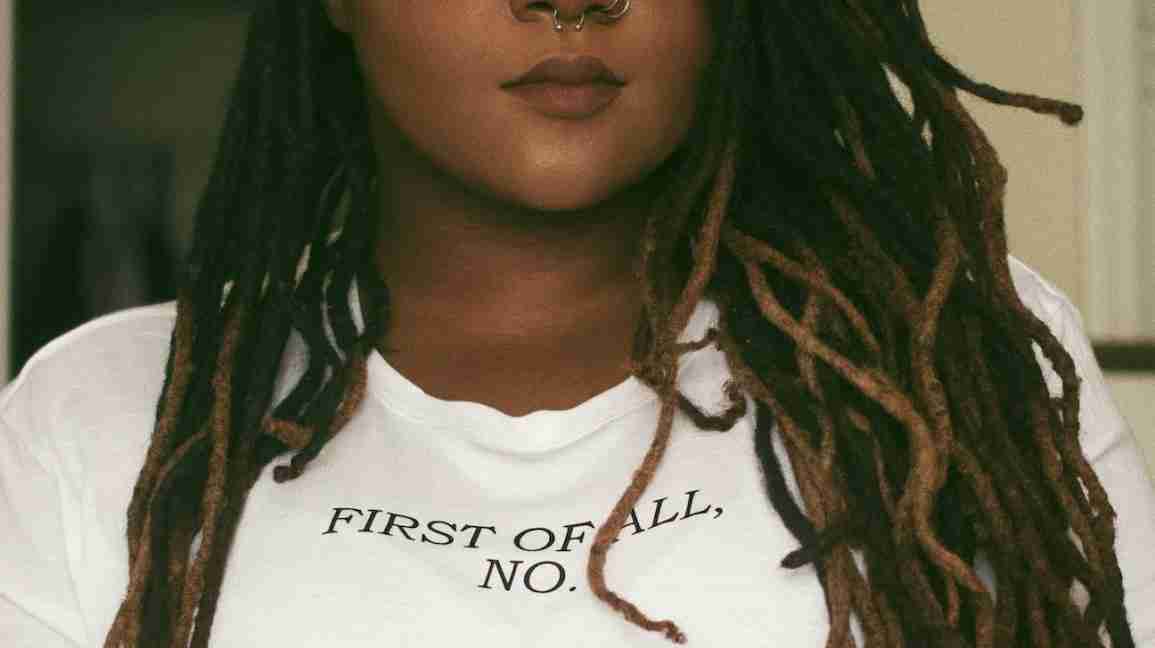

A graduate of Eastern University with a degree in Creative Writing and a minor in French from the Sorbonne, Imani Barbarin writes from the perspective of a black woman with cerebral palsy. She specializes in blogging, science fiction, and memoir.